Scaling Down Beats Scaling Up: The Algorithmic Attack on AI's Memory Wall

A few years ago, watching teams throw hardware at AI’s memory problems, I started thinking: what if the bottleneck isn’t hardware, but how we use it?

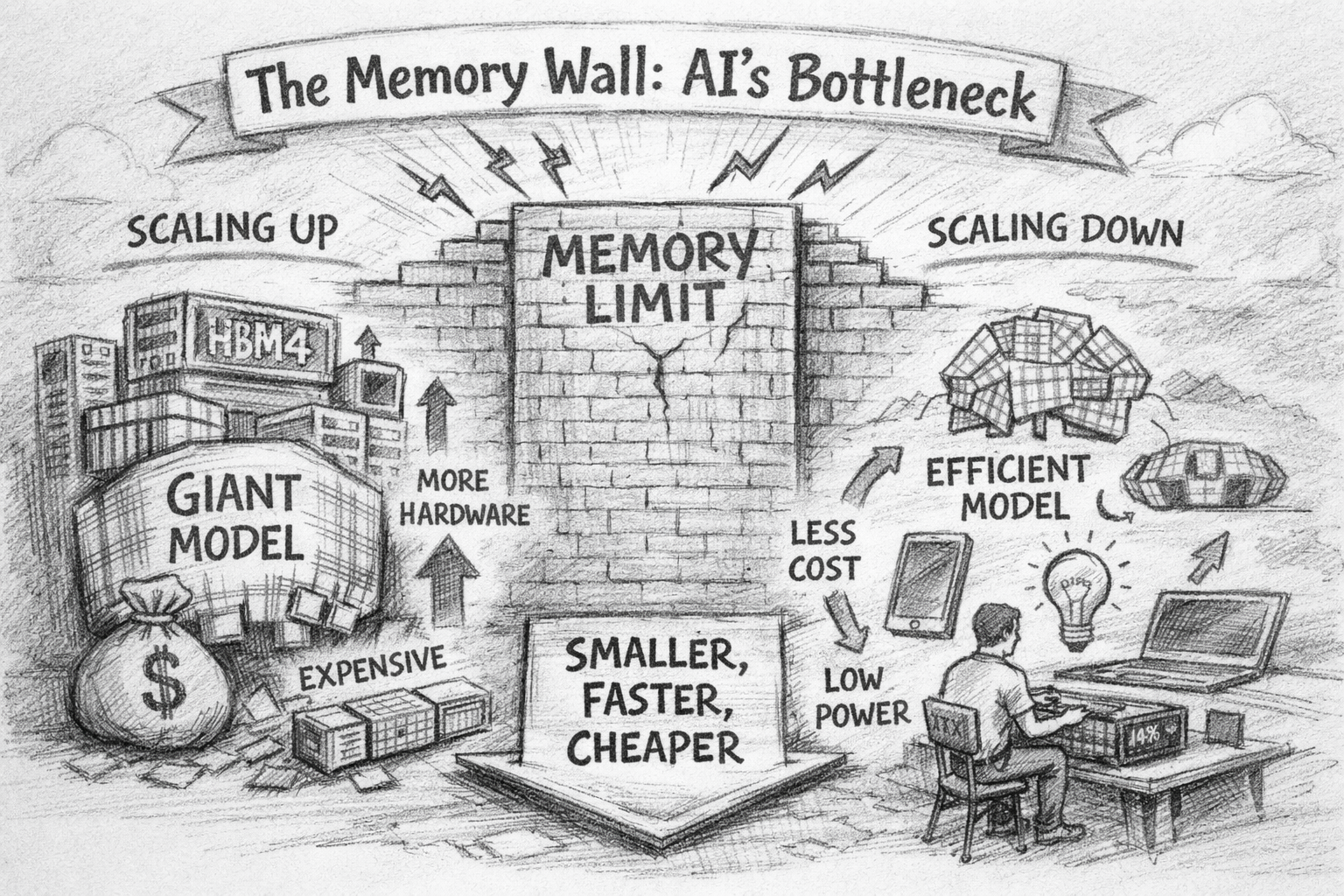

The AI industry is betting on hardware to solve the memory bottleneck. HBM4 is arriving. Processing-in-memory is in development. New accelerators are on the roadmap.

Meanwhile, LLM inference is hitting a wall due to memory constraints, not compute. Leading AI labs are losing billions annually on inference costs. Compute has scaled at 3x every two years while memory bandwidth has only scaled at 1.6x over the past two decades.

The diagnosis is correct. The prescription (wait for better hardware) is wrong.

The memory wall can be attacked algorithmically. Today. And the solutions reveal something deeper: the “bigger is better” era is ending.

Understanding the Memory Bottleneck

To attack the memory wall, you first need to understand why it exists.

Training has a severe memory problem. Adam, the optimizer used to train most LLMs, maintains two states per parameter for adaptive learning rates, consuming 2x the model size. With gradients and activations, a 7B model can require 60-80GB just for training state, far exceeding most GPU memory. The cost compounds: you can’t discard optimizer states mid-training, and gradient checkpointing trades memory for recomputation, slowing training 20-30%. Unlike inference, training batch sizes are constrained by learning dynamics, not just hardware.

Inference has a different bottleneck. LLM inference has two phases: prefill processes input tokens in parallel and can saturate GPU compute, but decode generates one token at a time, loading the entire model weights for each token.

The key metric is arithmetic intensity: operations per byte of memory accessed. Because decode performs relatively few operations per weight loaded, it has very low intensity. On an A100, you need an intensity of ~156 to be compute-bound. With batch size 1, decode runs at an intensity of ~2, nearly 80x below the threshold. The GPU sits idle, waiting for memory.

The Conventional Response

The industry’s default answer has been brute force: add more hardware, distribute the problem, or wait for the next generation.

Scaling hardware is the reflex. HBM4 promises 2x bandwidth. CXL enables memory pooling across nodes. But HBM costs 3x more per gigabyte than standard DRAM, with prices rising 20% annually. You can buy your way past the memory wall, but not cheaply, and not for long.

Model parallelism distributes models across devices. Tensor parallelism splits layers, pipeline parallelism splits stages, expert parallelism routes to specialized sub-models. These techniques work; they’re how frontier models get trained at all. But they add complexity, communication overhead, and don’t change the fundamental ratio of memory to compute. You’re not solving the problem; you’re spreading it across more machines.

Offloading moves data between GPU memory and CPU memory or disk. It works for batch workloads with high latency tolerance. For interactive inference, the round-trip kills response time.

Batching amortizes weight loads across concurrent requests, approaching compute-bound territory. It’s the standard production optimization. But it requires traffic to batch. For single-request, interactive inference, the memory wall remains.

All of these share a premise: the model is fixed, and we adapt the infrastructure to fit it. The alternative is to question the premise.

Attacking the Memory Wall Algorithmically

The conventional wisdom treats memory as a hardware problem requiring hardware solutions. But the constraints aren’t fundamental. Each bottleneck has an algorithmic attack surface.

Training: Memory-Efficient Optimization

Techniques like LoRA reduce memory for fine-tuning, but they don’t help with pre-training from scratch, where memory pressure is most severe.

The insight behind APOLLO: Adam’s per-parameter adaptation is overkill. Learning rate scaling at the channel or tensor level captures most of the benefit. By projecting into a low-rank auxiliary space, APOLLO achieves AdamW-level performance with SGD-level memory.

The practical impact: training LLaMA-7B from scratch on a single GPU with 12GB memory. This isn’t fine-tuning. It’s full pre-training, previously requiring eight A100-80GB GPUs, now possible on a consumer-grade GPU like the RTX 4090.

This isn’t an isolated result. GaLore, developed independently, takes a similar gradient projection approach and also enables 7B training on consumer GPUs. The convergence suggests the insight is robust: adaptive optimizers carry unnecessary state.

Inference: The Quantization Frontier

Weight quantization is the primary attack surface. The typical approach: quantize to 4-bit, lose a few points of accuracy, reduce memory 4x.

ParetoQ reveals this framing is wrong. By building a unified framework for quantization-aware training from 1-bit to 4-bit, we discovered the Pareto frontier isn’t monotonic. At 3-4 bits, the quantized model is essentially a compressed version of the original. But at 2 bits and below, the representations change fundamentally. The model isn’t learning to compress. It’s learning to represent information differently.

ParetoQ’s 1.58-bit 600M model outperforms state-of-the-art 3B models. That’s 5x fewer parameters with better accuracy. Why? At extreme low bits, the model can’t rely on precise values, so gradients push toward distributed, redundant encodings. Constraint becomes architecture.

SpinQuant attacks a different bottleneck: outliers that blow up quantization error. SpinQuant’s insight: rotation matrices can reshape activation distributions without changing model outputs. The result: 4-bit quantization of weights, activations, and KV-cache with under 3% accuracy loss, where previous methods degraded by over 25%. SmoothQuant takes a similar approach, smoothing outliers between activations and weights to enable 8-bit quantization with minimal loss.

These techniques show what’s possible at 4-bit. But what if you train at low precision from the start? Microsoft’s BitNet validates the extreme quantization thesis: a 2B model trained natively at 1.58 bits fits in 400MB (versus 4GB+ for standard models) and runs efficiently on a single CPU.

Architecture: Memory-First Design

The approaches above optimize existing models. But what if you designed for memory constraints from the start?

MobileLLM explores this for sub-billion parameter models. The core finding: at small scale, architecture matters more than parameter count.

Conventional wisdom from large models suggests width matters more than depth. But at sub-billion scale, deep-thin architectures (more layers, smaller hidden dimension) consistently outperform wide-shallow ones. MobileLLM also exploits scaling asymmetries: embedding layers account for 20% of parameters in small models versus 3.7% in large ones, so weight sharing yields outsized savings.

The result: a 125M model running at 50 tokens/second on an iPhone, compared to 3-6 tokens/second for LLaMA-7B. MobileLLM isn’t a compressed LLaMA. It’s architecturally designed for memory-constrained deployment.

Microsoft’s Phi series proves the same point at slightly larger scale: a 3.8B model matching 7B+ performance through careful architecture and data choices.

The Broader Efficiency Toolkit

These techniques are part of a larger toolkit the field is developing. Mixture of Experts activates only a fraction of parameters per token, dramatically reducing memory bandwidth during inference. Distillation trains smaller models to mimic larger ones. Pruning removes weights post-training. Speculative decoding uses small draft models to improve throughput.

Each attacks a different surface. The most powerful approaches combine them: a quantized, pruned MoE model can be dramatically more efficient than any single technique alone.

The Scaling Down Thesis

These results, from our work at Reality Labs at Meta and from researchers across the field, share a pattern: memory “requirements” are often artifacts of suboptimal algorithms and architectures, not fundamental limits.

- APOLLO and GaLore cut optimizer memory through smarter gradient handling

- ParetoQ and BitNet show extreme quantization enables different, more efficient representations

- SpinQuant and SmoothQuant show quantization accuracy loss is largely a failure of handling outliers

- MobileLLM and Phi show small models with memory-first architecture compete with much larger models

The industry assumption has been: capability requires scale, scale requires memory, therefore we need more memory. But the algorithmic evidence suggests capability and scale are less coupled than assumed. When you attack memory constraints directly, capability per byte improves dramatically.

This isn’t an argument that scale never matters. Frontier capabilities (the bleeding edge of reasoning, knowledge, and generalization) still benefit from larger models. The question is how much capability you need for a given application.

For many production use cases, smaller models now match what required 10x the parameters just two years ago. A well-optimized 7B model handles summarization, Q&A, and translation comparably to a 70B model from two years ago. The scaling down thesis isn’t “big models are useless.” It’s “most applications don’t need frontier scale, and we’ve been paying frontier costs for commodity capabilities.”

The Opportunity

The memory wall is creating a wedge in the AI industry. On one side: a handful of labs with billions in capital racing to train ever-larger models. On the other: everyone else, locked out by infrastructure costs.

Algorithmic efficiency changes this dynamic.

Access democratizes. Pre-training a 7B model that once required eight A100s now runs on a single RTX 4090. The barrier to entry collapses. Academic labs, startups, and independent researchers can train foundation models, not just fine-tune them. More players training means more players contributing. The economics shift toward openness, not because of ideology, but because the math favors it.

On-device AI becomes real. A 125M model at 50 tokens/second on an iPhone isn’t a demo; it’s a product capability. Private, offline, instant AI for translation, writing assistance, accessibility, and coding. No cloud round-trips or per-query costs.

Unit economics become sustainable. Serving a 1.58-bit model costs a fraction of serving a 16-bit model. Startups can build AI products without hemorrhaging cash on inference. The path to profitability shortens from “eventually, at scale” to “now, at any scale.”

The next phase of AI won’t be defined by the biggest models. It’ll be defined by capability per dollar, capability per watt, capability per byte. The industry is betting on hardware. The algorithms aren’t waiting.